Views: 57 Author: Site Editor Publish Time: 2018-11-05 Origin: www.fuchun-casting.com

The quality of products is the basis for the survival and development of enterprises. Improving the quality of machined workpieces is an urgent task for every large-scale machined factory. How do we improve the quality of workpieces?

1. Improving the cutting level

In mechanical processing, when the workpiece is machined, the surface of the workpiece will form almost the same mark as the shape of the cutter and leave a large number of scales. It is easy to increase the roughness and reduce the quality of the workpiece surface. Generally speaking, in this case, in order to ensure that the roughness of the workpiece surface is controlled within an appropriate range, the radius of the cutting tool tip arc should be increased appropriately, and the feed of the cutting tool should be reduced appropriately, so that the height of the residual area of the cutting tool on the workpiece can be reduced as much as possible. This can effectively reduce the workpiece surface debris and scales, improve the quality of the workpiece surface.

2. Improving Cutting Speed

When a workpiece is machined, if the cutting speed is faster, the deformation degree of the workpiece can be reduced, and the faster the cutting speed, the smaller the deformation degree, which can effectively reduce the roughness of the workpiece surface. If the cutting speed is not fast enough, the workpiece will produce chip tumors in the cutting process, which will affect the surface quality of the workpiece.

3. Improving the Accuracy of Machining Equipment

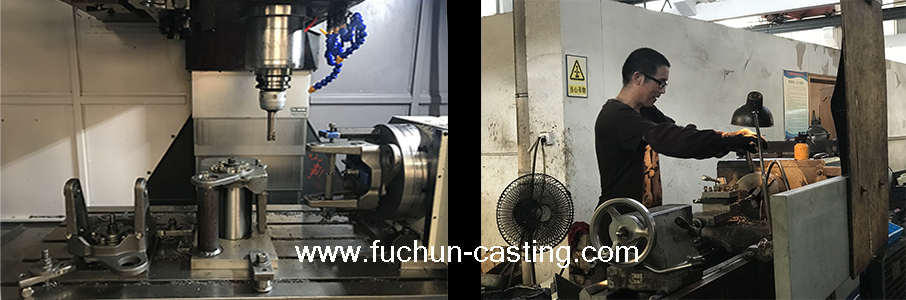

Workpiece processing is mainly accomplished by machine tools. The errors of machine tools will directly affect the accuracy of the workpiece. This requires ensuring the accuracy of the machine tool itself, which can effectively reduce errors. The error of tool and fixture will also affect the accuracy of the workpiece. Corresponding measures can be taken to reduce tool wear, which can also improve the accuracy of the workpiece.

We have a sound quality management system, the pursuit of excellence business philosophy, customer satisfaction-oriented, continuous improvement as the driving force, sincerely look forward to working with all customers to create the future for enterprises to provide high-quality products!

Besides casting materials, what causes the casting dimensional accuracy?

The cause of the surface blister of zinc alloy precision casting

Mechanical properties and machining requirements of stainless steel precision casting

What is the development status and future of agricultural machinery in China?

Do you think Metal 3D Printing will replace traditional casting technology?

Stainless steel precision casting temperature control and mold use

Is it possible to print high-speed rail with 3D printing technology?