Views: 35 Author: Site Editor Publish Time: 2018-12-05 Origin: www.fuchun-casting.com

1. The universality and harmfulness of burrs

Burr is the inevitable product of metal processing, which is difficult to avoid completely. The existence of burrs not only affects the appearance of products, but also affects the assembly and performance of products, speeds up wear and tear between equipment and reduces service life. With the development of high technology and the improvement of product performance, the requirement of product quality is more and more stringent. It is more important to remove burrs from mechanical parts. The existence of burrs has a great impact on product quality and product assembly, use, dimensional accuracy, shape and position accuracy. Seriously, it makes the whole set of products scrapped and the whole machine can not run.

2. What is the burr?

Burr - refers to a kind of redundant iron chips, commonly known as flying edges, which are formed in the process of cutting, grinding, milling and other similar chips when metal materials are extruded and deformed in the process of machining.

3. How to remove burrs?

The methods to solve the burr are as follows: only after the end of product processing, the process of removing burr is added. There are two main methods to remove burrs: chemical removal and physical removal.

Chemistry is mainly used for precise core workpieces with complex shape, deformity, high precision and high cost performance.

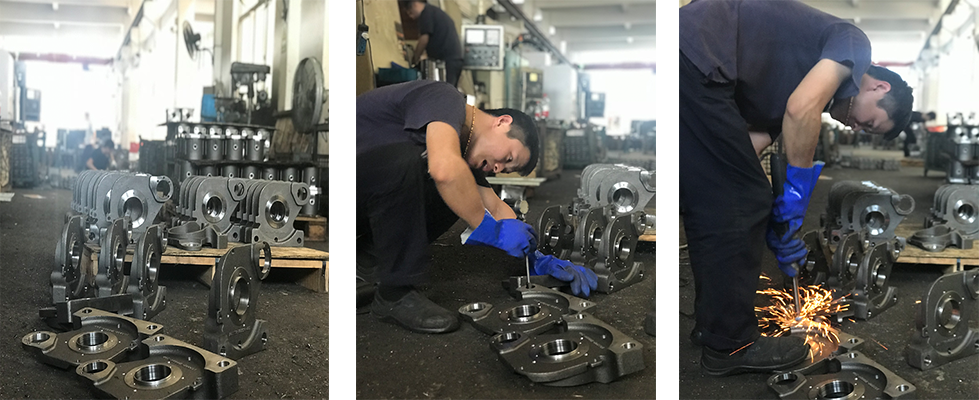

Physical classes are used for parts with rough surface and low dimensional accuracy, which are easy to remove by manual operation.

Chemical deburring process is a kind of soaking process, through the way of soaking to achieve the effect of deburring.

The process originated in Germany, which is widely used in the fields of automobile, aerospace and metal parts processing. The suitable parts are automobile parts, stamping parts, oil pump nozzle parts, textile parts, gear parts, bearing parts, electronic components, bearing parts, transmission parts, fasteners, CNC parts and so on.

This process mainly utilizes the difference between burr and the structure of workpiece itself, and achieves the effect of burr removal through the principle of vertical reaction. Our definition of burr is that the thickness of burr is less than 20 wires, which has nothing to do with the height of burr.

Compared with the traditional deburring process, the process is far superior to the traditional process in reliability, repeatability, stability, environmental protection and other aspects; efficient and time-saving, improve product surface finish, safety and reliability, environmental protection and economy, simple operation, can enhance the anti-corrosion and anti-corrosion ability of products.

Physical deburring mainly includes rough (hard contact) cutting, grinding, file, scraper, ordinary (soft contact), belt grinding, grinding, elastic grinding wheel grinding, polishing and washing and other processes with different degrees of automation. The quality of the processed workpiece is often not guaranteed; production costs and personnel costs are very high.

Besides casting materials, what causes the casting dimensional accuracy?

The cause of the surface blister of zinc alloy precision casting

Mechanical properties and machining requirements of stainless steel precision casting

What is the development status and future of agricultural machinery in China?

Do you think Metal 3D Printing will replace traditional casting technology?

Stainless steel precision casting temperature control and mold use

Is it possible to print high-speed rail with 3D printing technology?